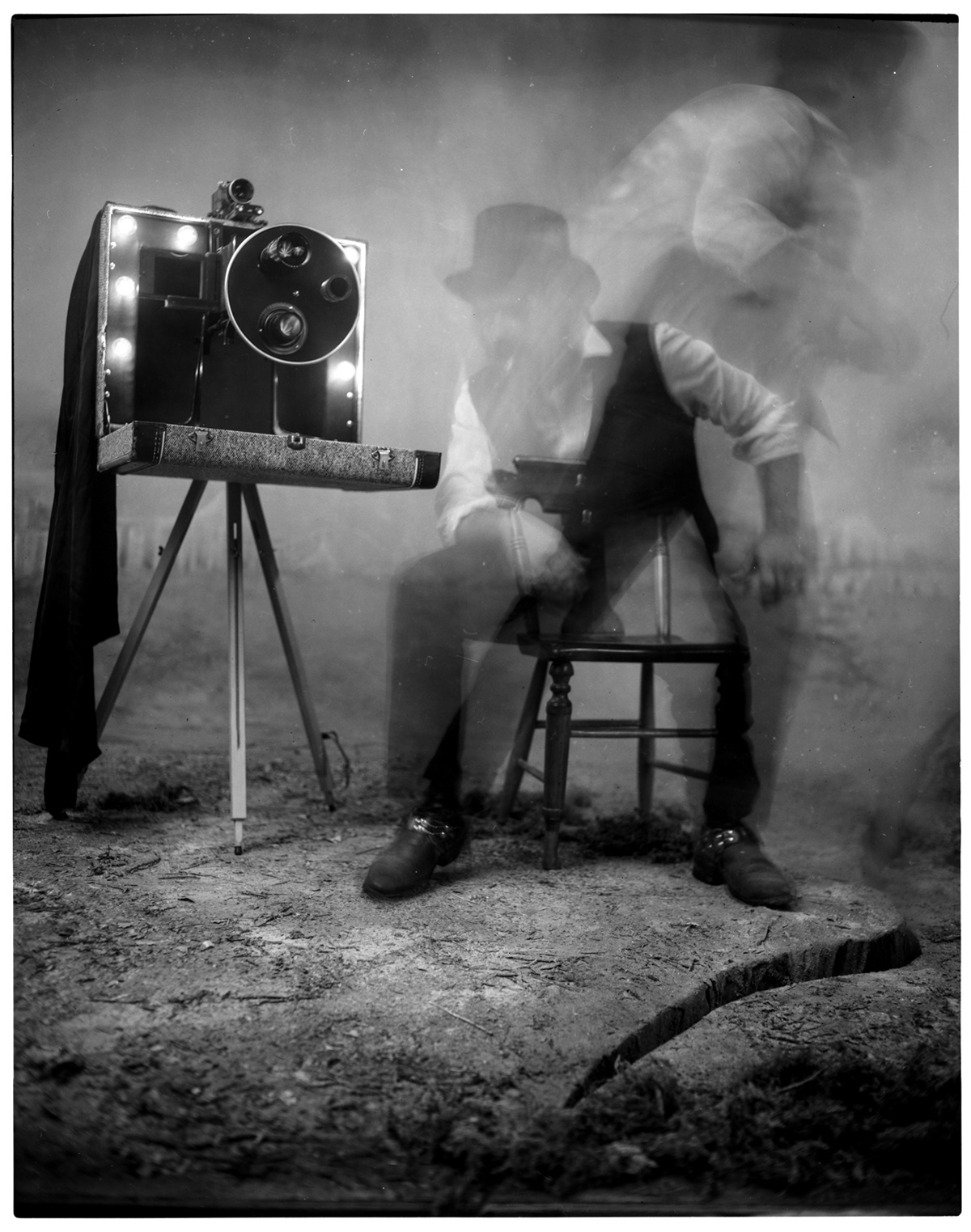

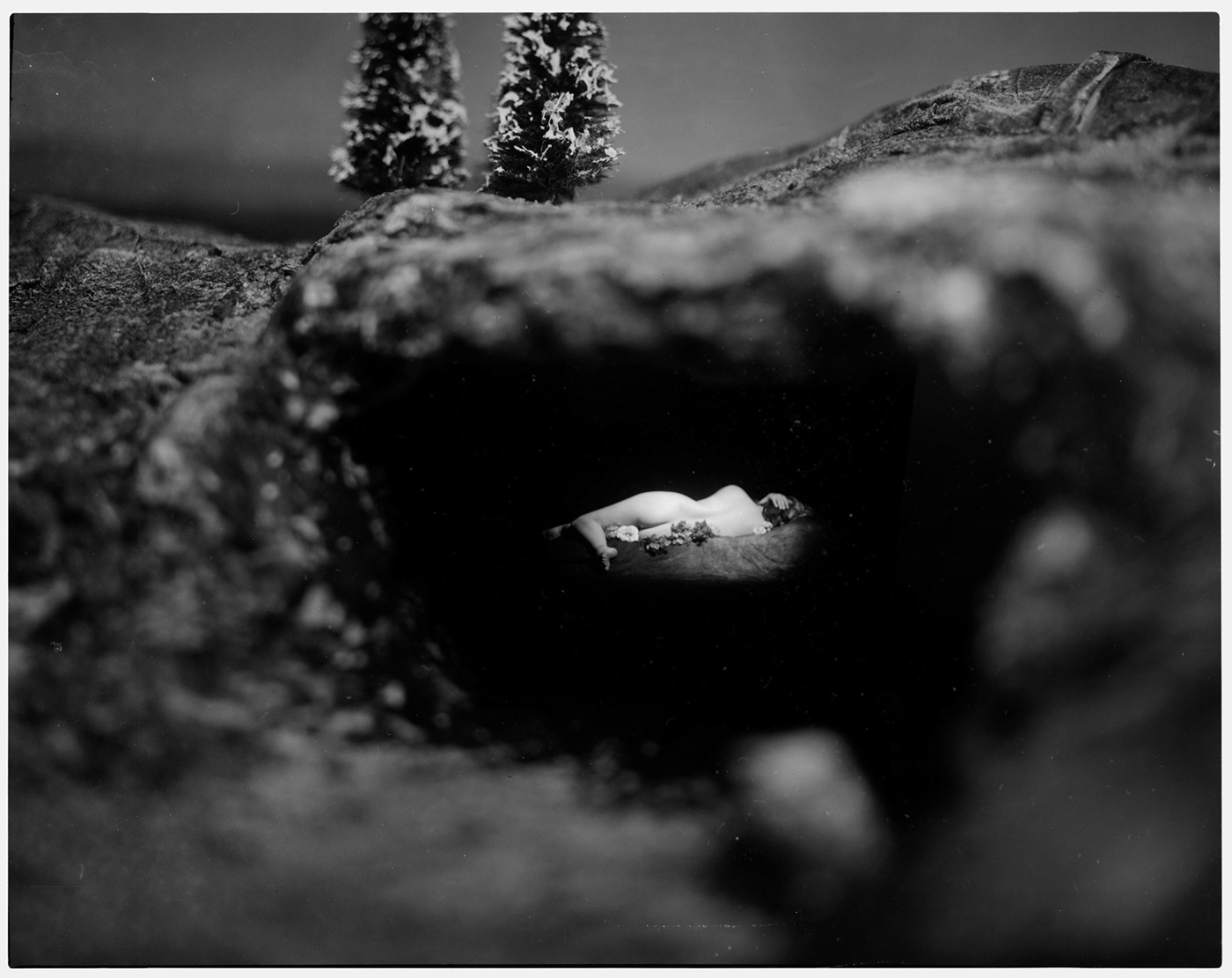

Orpheus + Eurydice

From Scott McCormick's solo exhibition, "Orpheus"

I:I Artist Statement — “Orpheus” is the culmination of a year and a half of work from artist Scott McCormick. Mining the subject matter, compositional geometry, and visual aesthetic of 19th century French academic painters like Bouguereau, Cabanel, and Tissot, McCormick’s epic work defines an emerging and innovative photographic style. Utilizing both digital compositing and film photo techniques, combined with his own large, custom-built sets, expansive props, and headdresses, each image is a complex orchestration of divergent elements and techniques. The intricate composite images — sometimes utilizing over 600 photographs immixed together — achieve a sense of silent frenzy. The process of combining digital and film photography has allowed the artist to prospect a “prophecy-of-self” through his time spent learning.

I.II In early stages of the work, McCormick immersed himself in the folklore of Greek, Slavic, and Mayan cultures. This sparked an exploration of the parallel between the art, as it was revealing itself, and the grandiose mythologies emblazoned on the world’s memories and creations. Throughout his process, the connection to these cultures illuminated itself wholly in the revelation that McCormick’s life as a musician, poet, and artist was reflective of the story of Orpheus. In, perhaps a divine sense of fate, each piece had a minimal predetermined direction at inception, and the connection (or purposeful disconnect) was often only discovered or understood after the photograph was finished.

I.III Shedding the established traditions and procedures of his commercial work practice, McCormick limited the amount of preparatory sketching, and planned only the general idea of each photo, allowing each of the photographs to take on a separate life, unfolding in a through-composed storyline. The works in this exhibition explore ascension, disconnection, divergence, and a powerful sense of feeling for the audience all while thoroughly re-telling the story of Greek legend, Orpheus.

—

CREDITS

Photographers: Scott McCormick & Merne Judson III Set Building & Design: Justin Hicks & Scott McCormick Backdrop Painting: Katie Webster Camera Development & Design: Justin Hicks, Joel Blaine, and Scott McCormick Electrician: Jeff Engelstad

In sweet music is such art: killing care and grief of heart fall asleep, or hearing, die.

Son of the Thracian King Oeagrus (some variations claim Apollo as his father) and the Muse Calliope, was the most famous poet and musician who ever lived. Apollo presented him with a lyre, and the Muses taught him its use, so that he not only enchanted wild beasts, but made the trees and rocks move from their places to follow the sound of his music. At Zone in Thrace a number of ancient mountain oaks are still standing in the pattern of one of his dances, just as he left them. After a visit to Egypt, Orpheus joined the Argonauts, with whom he sailed to Colchis in search for the Golden Fleece. His music helping them to overcome many difficulties including freeing the Argonauts allowing them to avoid the beautiful songs of the Sirens. On his return, he married Eurydice, whom some called Agriope, and settled among the savage Cicones of Thrace.

(1) One day, near Tempe, in the valley of the river Peneius, Eurydice met Aristaeus, who tried to force her. She trod on a serpent as she fled, and died of its bite; but Orpheus boldly descended into Tartarus, hoping to fetch her back. He used the passage which opens at Aornum in Thesprotis and, on his arrival, not only charmed the ferryman Charon, the Dog Cerberus, and the three Judges of the Dead with his plaintive music, but temporarily suspended the tortures of the clanmeal; and so far soothed the savage heart of Hades that he won leave to restore Eurydice to the upper world. Hades made a single condition: that Orpheus might not look behind him until she was safely back under the light of the sun. Eurydice followed Orpheus up through the dark passage, guided by the sound of his lyre, and it was only when he reached the sunlight again that he turned to see whether she were still behind him, and so lost her for ever.

(2) When Dionysus invaded Thrace, Orpheus neglected to honour him, but taught other sacred mysteries and preached the evil of sacrificial murder to the men of Thrace, who listened reverently. Every morning he would rise to greet the dawn on the summit of Mount Pangaeum, preaching that Helius, whom he named Apollo, was the greatest of all gods. In vexation, Dionysus set the Maenads upon him at Deium in Macedonia. First waiting until their husbands had entered Apollo’s temple, where Orpheus served as priest, they seized the weapons stacked outside, burst in, murdered their husbands, and tore Orpheus limb from limb. His head they threw into the river Hebrus, but it floated, still singing, down to the sea, and was carried to the island of Lesbos.

(3) Tearfully, the Muses collected his limbs and buried them at Leibethra, at the foot of Mount Olympus, where the nightingales now sing sweeter than anywhere else in the world. The Maenads had attempted to cleanse themselves of Orpheus’s blood in the river Helicon; but the River-god dived under the ground and disappeared for the space of nearly four miles, emerging with a different name, the Baphyra. Thus he avoided becoming an accessory to the murder.

(4) It is said that Orpheus had condemned the Maenads’ promiscuity and preached homosexual love; Aphrodite was therefore no less angered than Dionysus. Her fellow Olympians, however, could not agree that his murder had been justified, and Dionysus saved the Maenads’ lives by turning them into oak-trees, which remained rooted to the ground. The Thracian men who had survived the massacre decided to tattoo their wives as a warning against the murder of priests; and the custom survives to this day.

(5) As for Orpheus’s head: after being attacked by a jealous Lemnian serpent (which Apollo at once changed into a stone) it was laid to rest in a cave at Antissa, sacred to Dionysus. There it prophesied day and night until Apollo, finding that his oracles at Delphi, Gryneium, and Clarus were deserted, came and stood over the head, crying: ‘Cease from interference in my business; I have borne long enough with you and your singing!’ Thereupon the head fell silent. Orpheus’s lyre had likewise drifted to Lesbos and been laid up in a temple of Apollo, at whose intercession, and that of the Muses, the Lyre was placed in heaven as a Constellation.

— From Robert Graves’ “The Greek Myths”

Photographed on: Large format: (4×5) Graflex SpeedGraphic | Medium format: Mamiya RB-67 | CatLabs and Ilford films

Lighting: Paul C. Buff DigiBees | Overhead tungsten bulbs

Lighting: Paul C. Buff DigiBees | Overhead tungsten bulbs

Jean-Paul Sartre — At times discreetly, at times disgustingly, I yielded to the most fatal temptation whenever I could no longer bear it: as a result of impatience, Orpheus lost Eurydice; as a result of impatience, I lost myself.

This series of images is for a solo exhibition by Scott McCormick titled "Orpheus."

Thank you for checking it out.